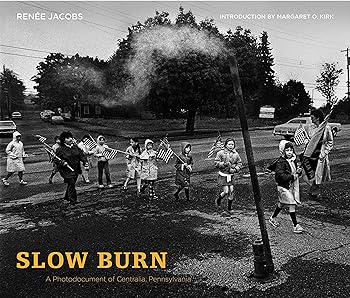

By 1984, the fate of Centralia, Pennsylvania was sealed. Through a combination of bureaucratic apathy and incompetence, the mine fire had burned continuously since 1962. It threatened the homes, health, and safety of the people who lived there.

In August of 1983, an overwhelming majority of the Centralia’s residents had voted to relocate the town. Now the federal government had approved $42 million to get the job done. The Centralia Mine Fire Acquisition Relocation Project had begun.

At first, relocation was voluntary. When a household expressed interest in leaving, an entourage would descend upon the property and begin assessing it. A fair market offer would be extended to the owner and assistance provided for relocating the household.

If the offer was accepted, the family would be compensated and relocated, usually to a neighboring town. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania then took ownership of property.

Voluntary relocations continued for years. Often there was a domino effect. One family on a block would decide to leave. Their home would be condemned, boarded up, and spray painted to indicate it was slated for demolition. This sent a clear message to their neighbors, causing others to leave too.

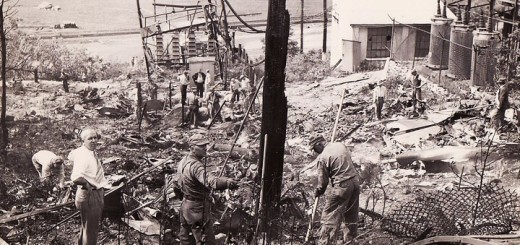

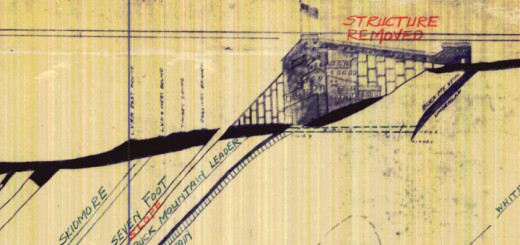

When enough homes on a block had been vacated, a demolition crew was brought in. They leveled the structures, backfilled the basements, and performed basic landscaping. Occasionally, the remaining row homes on a block would have to be buttressed after the neighboring homes were torn down.

This process is visible in the film Made in USA. As the protagonists in the film walk through Centralia PA, boarded up homes can be seen. Near the end of the clip, a home is slowly being demolished. According to writer David DeKok, by the end of 1986 there were less than 50 homes standing in the town.

The effort to relocate the remaining residents of Centralia was contentious. Those who wished to stay often felt betrayed when others left. Some viewed leaving as a triumph. The government was paying for their properties which had been threatened by the mine fire. While it wasn’t easy, they had a chance to start over. Others saw it as giving up in the face of adversity. Many of those same feelings exist today with current and former Centralia residents.

For those who rented properties, the conflict was even more heated. Some landlords wished to sell their properties to the state, even as their tenants wished to stay. In 1987 eviction notices were sent to those who rented properties from owners who wished to sell. What had begun as a voluntary relocation was fast becoming mandatory.

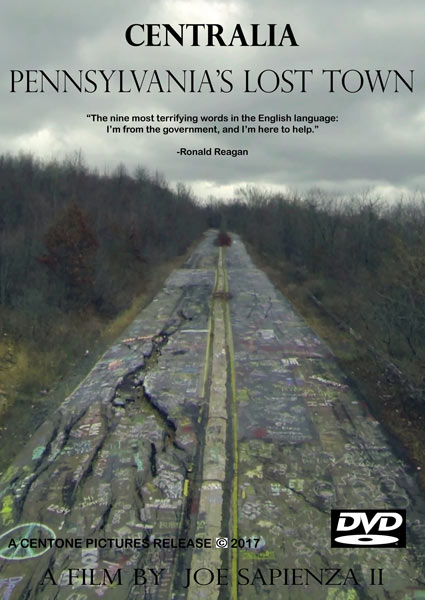

It’s important to note that the mine fire hadn’t stopped when the Relocation Project began in late 1983. It continued to rage throughout the 1980s. Noxious gases, venting steam, and ground subsidence were all common occurrences. By the early 1990s, it was clear that the stretch of Route 61 just south of the borough would need to be closed. The mine fire had badly damaged it. Today this abandoned stretch of Route 61 is known as the Graffiti Highway.

The population of Centralia PA continued to dwindle. In 1992, Pennsylvania Governor Robert P. Casey declared eminent domain over the remaining properties within the town. This was done out of concern for the safety of those living there and because of the liability the state might face should someone be injured by the mine fire. Pennsylvania forcibly acquired the deeds to their lots and worked to evict them from their homes.

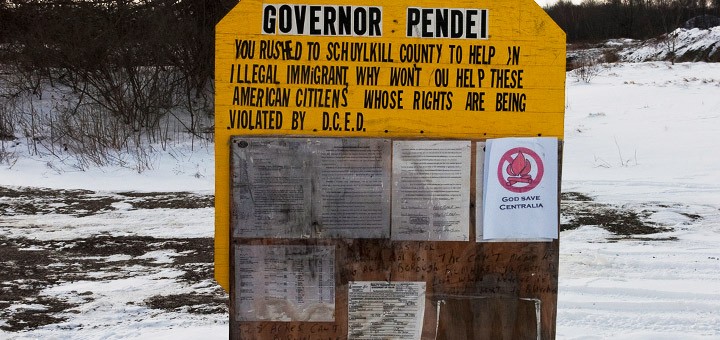

Still some people, like Carl and Helen Womer, refused to relocate. Several families banded together and mounted a legal challenge to the government’s effort to evict them from their properties. Others, fearing an expensive legal battle, finally relented and accepted relocation.

By 1995, the lawsuit by residents to stop the eviction went to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The evictions were upheld. However, when a new Pennsylvania governor, Tom Ridge, was elected his administration wanted nothing to do with the fight. The evictions were put on hold.

There was one financial upside for those who stayed. After the state took the deeds to their homes, these residents no longer had to pay property taxes. They also lived on their state owned properties rent free.

At the time of the 2000 census, there were only 21 people left in Centralia Pennsylvania. In 2002 the United States Postal Service revoked the town’s ZIP code, 17927, due to a lack of population. The post office had earlier been demolished in 1997.

Centralia was becoming a ghost town and, as a result, attracting curious tourists. In 2006, TriStar Pictures released the film, Silent Hill. Centralia’s long burning underground mine fire was part of the inspiration for the film. This dramatically increased the number of people visiting the town. It also irritated many of the remaining residents who, after years of fighting to stay in their homes, simply wanted to be left alone to live their lives in peace.

Centralia continued to capture the public’s imagination with the release of the 2007 film, The Town That Was. The movie tells the history of the mine fire and the story one of the last remaining residents, John Lokitis Jr. It was only a few years after this in 2009, that the state would resurrect its efforts to evict the last people living in Centralia.

- Learn about the connection between Silent Hill and Centralia PA

- Explore the documentary film The Town That Was

Some, like John Lokitis Jr., finally left the town after receiving eviction notices. Others stayed and fought on. They resumed their legal efforts to block the eviction process. This would drag on until 2013. In that year, the state finally agreed to settle the lawsuit with the eight remaining residents. They won the right to stay in their homes for the rest of their lives. When they die, their properties will pass into state control. Today, there are currently six residents left in Centralia, PA.

The history of Centralia since 1962 is not a happy one. Nevertheless, it is important that we know, understand, and appreciate it. Each year, thousands of people visit what is left of the town. Many leave wanting to know more and wishing that they could do something to help.

In the fall of 2014, something amazing happened in Centralia. A group of volunteers along with current and former residents came together to cleanup the town. During the day, they shared stories and removed several tons of trash. Efforts like these show that there is still hope for Centralia’s future. While the town is nearly gone, many people care about this place and wish to keep it’s memory alive for years to come.

Want to learn more about Centralia’s history? Be sure to also read about the history of Centralia before 1962, 1962 to 1977, and 1977 to 1984.

I really whant to go there

me too ps i <3 silent hill