By 1977, the residents of Centralia Pennsylvania stood at a crossroads. For 15 years, a mine fire had uncontrollably burned at the edge of their town. Time was quickly running out.

Many methods had been tried to stop the fire and mitigate the deadly gases it produced. Early on a trench had been dug with the hopes of halting it. When this failed, use of an experimental fly ash barrier was ordered. This was doomed to fail as well.

In late 1976 the Bureau of Mines was under increasing pressure from Centralia’s residents to take action. Boreholes drilled as part of the earlier efforts to combat the fire were steaming and hot to the touch. The fire was moving under the town, threatening the health and safety of those living there.

News of the deadly mine gases in Centralia PA had reached the news media by 1977. The Bureau of Mines scrambled to act. Late that year they began drilling new boreholes to determine the integrity of the fly ash barrier. The results were not comforting. While several areas were intact, many were partially compromised or non-existent.

Work on shoring up the fly ash barrier began in May of 1978. Almost immediately, the residents of Centralia began pushing for greater transparency. Many wanted more boreholes to be dug in order to reveal the full extent of the fire.

Others pushed for more drastic solutions. They wanted an new trench dug and filled with incombustible material. This would form an underground wall to keep the fire from reaching the town. Unfortunately, such an option would require destroying some of Centralia’s homes. This provoked immediate backlash from one of town’s most vocal residents, Helen Womer.

In June of 1979 carbon dioxide and other deadly gases were detected in the homes of John Coddington and David Lamb. By December the heat and steam from the Centralia mine fire threatened Coddington’s gas station, forcing it to close.

For the next several years, bureaucratic infighting paralyzed any effort to mitigate the growing danger in Centralia Pennsylvania. Carbon monoxide detectors were given to residents to monitor the air in their homes. Although, given the high cost of the devices, many families were forced to share them. And, when the alarm rang indicating a problem, the only remedy was to open a window and ventilate the house. This was particularly uncomfortable during the cold winter months.

In 1980, mine fire gases were detected at the St. Ignatius School along Locust Avenue, raising the concerns of the parents whose children attended there. Flushing of the mine tunnels near the school was ordered, as well as the installation of mine fire ventilation pipes. Like the other attempts to deal with the fire, hopes for success quickly faded. The fire was now estimated to be under 150 acres of land.

Centralia PA’s residents increasingly grew frustrated. Some, like John Coddington, called for their homes to be bought and families relocated out of harm’s way. Others, like Helen Womer, denied there was any problem and stubbornly refused to budge.

1981 would become a watershed year for the Centralia mine fire disaster. In some areas the fire was now visible at the surface. When measured, the temperatures were in excess of 1200 degrees Fahrenheit!

On Valentine’s Day of that year Todd Domboski fell into a steaming hole caused by the mine fire and was nearly killed. It just so happened that key politicians were in the town that day and observed the aftermath of the incident first hand.

The trouble continued as more residents were overcome by the carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide seeping into their homes. On March 19, 1981, John Coddington was overcome by the gases. Thankfully, he was rushed to the hospital and made a full recovery.

Momentum began to build for more decisive action. On March 30th, Pennsylvania’s Governor Thornburgh flew into Centralia PA on a helicopter. Though a political stunt, it helped to focus even more attention on the beleaguered town and its long suffering residents.

The people of Centralia were beginning to mobilize as well. David Lamb, along with others, formed the Concerned Citizens Action Group Against the Centralia Mine Fire. Together they would push for a consensus regarding what was to be done to save the town.

A referendum was schedule for May to determine if residents wished to stay and have the fire excavated or relocate away from danger all together. While the vote had little legal weight, the results were clear. The overwhelming majority of Centralia’s residents wished to relocate.

By the end of 1981, 29 families has been declared eligible for relocation. The government would purchase their homes and support them in moving out of the most endangered areas of Centralia, Pennsylvania.

The momentum continued to build in 1982. Money was allocated to drill new boreholes around the town in order to determine the exact boundaries of the mine fire. Using the results of this, a plan would be developed and presented to Centralia.

Nevertheless, the people living in the town were as conflicted as ever. While many pushed to leave, others fought tooth and nail to stay. Infighting and threats caused the Concerned Citizens group to fray, while Borough Council meetings devolved into shouting matches.

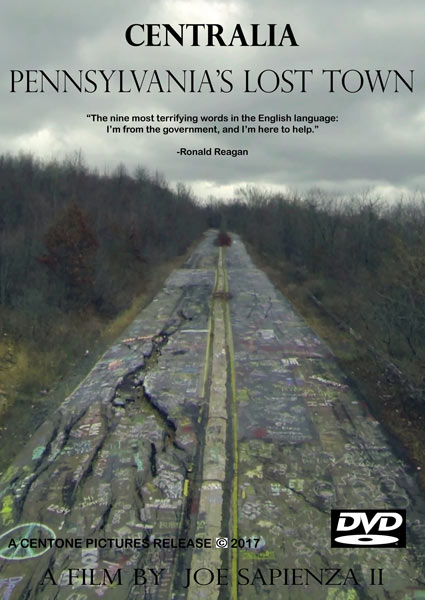

The mine fire continued to progress quickly, spewing dense, hot gases into the air and causing ground subsidence. By 1983, the neighboring town of Byrnesville was threatened, as was the main road through the area, Route 61. Residents were especially spooked by the fire nearing a gas pipeline and the prospect of it exploding.

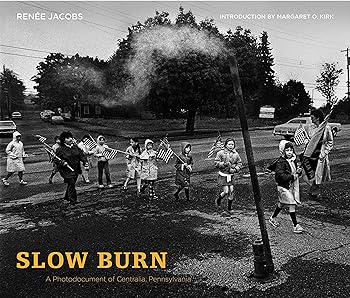

With tensions mounting, a novel idea was proposed. The town would come together on March 6, 1983 in a show of solidarity. Dubbed “Unity Day,” the event would be the perfect opportunity to rally residents, grab the media’s attention, and apply pressure to politicians.

While Unity Day certainly had an impact, it was not enough to save Centralia PA. On July 12, 1983 the results of the study and plan were announced. The mine fire was determined to be, without a doubt, under the town and affecting at least 195 acres. Total excavation of the fire would cost $660 million and destroy significant numbers of homes.

The numbers were shocking, given the relatively little money it would have taken to extinguish the mine fire in the 1960s. Residents were asked to vote on relocation on August 11th. Once again, the vast majority voted “yes.” The town’s fate was sealed.

$42 million was set aside by the federal government to initiate the Centralia Mine Fire Acquisition Relocation Project. Residents began to voluntarily leave in late 1983, with the pace picking up dramatically in 1984.

In the last of our articles about the history of Centralia Pennsylvania, we’ll look at events happening from 1984 to the present day. Be sure to also read about the history of Centralia before 1962 and 1962 to 1977.

OMG! Its so cool. Its just like the movie Silent Hill! And its actually burning! How exactly did it start to burn?